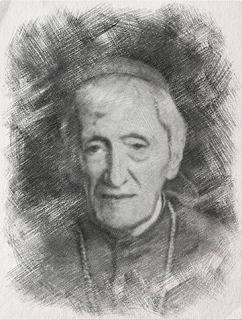

John Henry Newman and Liberalism

What with the “canonization”

of John Henry Cardinal Newman (1801-1890) coming up in a couple of weeks, we

thought we would add our two cents as well as a few hundred words into the

discussions that are raging. (Canonization does not "make" someone a saint; it is a certification process.) By and

large, the discussion seems to be whether Newman was a liberal or a

conservative. From the interfaith

viewpoint, however, it seems more to the point whether Newman was in agreement

with the Just Third Way.

|

| John Henry Newman |

For the record, Newman

was opposed to liberalism of any kind, even that with which he agreed! As he

explained in an appendix (not generally included these days) to his Apologia

Pro Vita Sua (1864), he opposed liberalism as an Anglican, supposing the

Anglican position to be conservative. After his conversion to Catholicism, he

realized that what the English political and religious establishment regarded

as conservative was really a different form of liberalism, and rejected it.

Newman then

expressed puzzlement at the fact that Charles Forbes René de

Montalembert (1810-1870) and Father Jean-Baptiste

Henri Dominique Lacordaire (1802-1861), both former associates of Hugues-Félicité Robert de

Lamennais (1782-1854) — the founder of liberal

Catholicism — agreed with Newman in repudiating de Lamennais’s liberalism and

English “conservative” liberalism. At

the same time, both Montalembert and Lacordaire continued calling themselves

liberals! Newman concluded by saying that it pained him to disagree with two

such eminent and orthodox thinkers, and supposed that they must mean something

else by the term liberalism. As

Montalembert said later,

|

| Montalembert |

To new and fair practical

notions, honest in themselves, which have for the last twenty years been the

daily bread of Catholic polemics, we had been foolish enough to add extreme and

rash theories; and to defend both with absolute logic, which loses, even when

it does not dishonour, every cause. (Montalembert, from his Life of Lacordaire, quoted by John Henry

Cardinal Newman, “Note on Essay IV., The Fall of La Mennais,” Essays Critical and Historical. London: Longmans, Green, and Co., 1897,

173-174.)

That appears to

be the case. Alexis-Charles-Henri

Clérel de Tocqueville (1805-1859) described three types of liberal

democracy in Democracy in America (1835, 1840). These were 1) French or European in which the

collective or State is sovereign, 2) English, in which an élite is

sovereign, and 3) American, in which the human person under God is sovereign.

Interestingly, de

Tocqueville worked with de Lamennais in the legislature during the brief Second

French Republic. De Tocqueville

recognized de Lamennais’s ability and even shared some of the same goals, but

thought he was an arrogant jackass: “He has pride enough to walk over the heads

of kings and bid defiance to God.” (Alexis de Tocqueville, The Recollections of Alexis de Tocqueville. Cleveland, Ohio: The World Publishing

Company, 1959, 191.)

|

| Lacordaire |

The American type

of liberal democracy is embodied in the original intent of the U.S.

Constitution, which almost every pope since Pius IX has approved — although not

using the word liberal to describe it. Pius IX modeled the first constitution

of the Papal States on the U.S. Constitution.

This was the “Fundamental Statute,” which William Ewert Gladstone (1809-1898)

erroneously thought was derived from the unwritten English constitution. Leo XIII kept a special copy of the

Constitution, a gift of Grover Cleveland at the suggestion of Cardinal Gibbons,

in his personal apartments, and showed it to favored visitors.

Newman continued

to reject the term liberalism, but eventually reached some sort of accommodation

with American liberalism, most likely through his lively “debate” (we’re being

polite) with Orestes Augustus Brownson (1803-1876). Like Montalembert, Lacordaire, and even

Blessed Antoine-Frédéric Ozanam (1813-1853) and Newman himself, Brownson at

first supported de Lamennais and then condemned him in his unique Brownsonian

manner. Newman even invited Brownson to

be on the faculty of the Irish university he was trying to put together,

although probably fortunately for Brownson’s temper and Newman’s peace of mind

Brownson declined.

|

| Gibbons |

In Testem

Benevolentiae Nostrae (1899), Leo XIII carefully distinguished American

liberal democracy (“Americanism”) as a political theory from Americanism

applied to religious doctrine (modernism and socialism). This was largely as a result of a distorted

translation into French of a biography of Brownson’s friend Father Isaac Hecker

(1819-1888) in which the translator Abbé Felix Klein (1862-1953) — possibly

inadvertently — made the mistake of using terms that meant one thing in

American liberalism and almost the exact opposite in French liberalism.

This gave the

French modernists a weapon against the more orthodox elements in the Church. Some conservative French prelates were calling

the Americans Archbishop John Ireland (1838-1918) and James Cardinal Gibbons (1834-1921) heretics. The French conservatives appeared to assume

that when Ireland and Gibbons called themselves progressive (another word that

has completely changed its meaning) and liberal they meant the exact opposite

of what the Americans actually meant.

Gibbons and

Ireland were both hurt that Leo XIII demanded their explicit submission to Testem

Benevolentiae Nostrae (which they gave after trying to figure out what was being

condemned), but socialists, modernists, liberals, and progressives have used

the different meanings of liberalism to spread confusion and obscure the

inroads of socialism and modernism down to the present day.

So, yes, Newman

was a liberal . . . but not in any sense either he meant or today’s liberals

mean the term.

#30#

Comments

Post a Comment